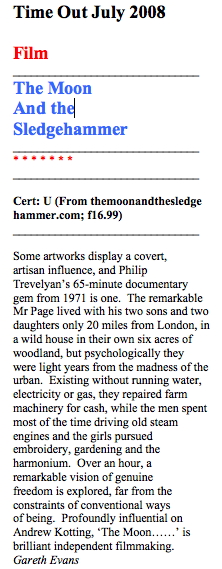

Critics’ Reviews

theguardian Film

The Moon and the Sledgehammer: the cult film about a Sussex family who hid in a forest

In 1969, Philip Trevelyan filmed the beguilingly strange life of the Page family, who lived off-grid and rode steam engines round their wood. The director talks about how the film changed his life

‘I felt that Jim and Kathy had a relationship of some sort which was secret’

Patrick Barkham @patrick_barkham

Patrick Barkham @patrick_barkham

As pop music blares and cars rush past, the camera lurches into a wood at the road’s edge and, through rustling foliage, reveals a strange scene: giant spanners, a discarded bike and a piano outside a primitive tin-roofed cottage. The bucolic chirp of sparrows is shattered by a gunshot.

From the first moment of the cult documentary, The Moon and the Sledgehammer, we are taken into a disturbing, marginal and strangely marvellous world: the home of the Page family, who live without electricity or running water in a wood in Sussex. It is 1969 and “Oily” Page is a theatrical septuagenarian who lives with four grown-up children in the style of 1869: they’re not hippies who’ve gone off grid, but the last members of an agricultural community driven to extinction by modern machines.

The film has attracted a following over subsequent decades, and not just among back-to-the-land types or aficionados of the spectacular traction engines the Pages ride in their wood. A new digital version will be shown at the Brighton festival this weekend alongside a question-and-answer session with Philip Trevelyan, its director.

This is just as well, because the film raises dozens of questions: where is Mrs Page? Why are the grown-up children still living with their father? What does Mr Page mean by his gnomic utterances (“he’s like a long lane without a turning”; “man will invent things to destroy himself”)? Is he a fool or a sage? And what do the Pages possess that we have lost?

FacebookTwitterPinterest

FacebookTwitterPinterestWhen I meet Trevelyan, now 72, he has just finished pulling dock leaves on his organic farm – back-breaking work. In 1975, he and his wife Nelly sold their London flat and bought a 53-acre farm in North Yorkshire. “I fell into ‘Oily’ Page work,” he says, wondering aloud – in a characteristically open-ended fashion – if his career change was inspired by his encounter with the family.

The son of painter Julian Trevelyan and the potter Ursula Mommens, Trevelyan grew up in rural Sussex, studied fine art and film, and was working for Granada TV when a friend met the Pages by chance at a rural auction. Trevelyan visited them and was entranced by their “wonderful” home surrounded by nature. He befriended the family, took stills of them and then, with producer Jimmy Vaughan, raised “well over £10,000” to make a film. In 1969, Trevelyan took a crew of four and they lived in an old Commer van in the Pages’ wood for a month.

‘The more we stop doing things for ourselves, the more lifeless we become’ … Trevelyan

It was in the weeks before the moon landing. “Waste of time, waste of money,” says Mr Page. “It’s a good job the moon’s well up there too, I’ve got room enough to swing a sledgehammer without hitting him.” Such remarks sound cryptic, but Trevelyan believes the Pages’ criticism of “push-button” machines (and now computers) reveal what we’ve lost – not just jobs, but a kind of work that was satisfying, communal and even pleasurable.

“We’ve throttled our enjoyment of work by buying so many ‘convenient’ machines and different ways of not doing work,” says Trevelyan. “The more we stop doing things for ourselves, the more lifeless we become. There’s terrific life expressed by the family in that film – gaiety, innocence and openness.”

Trevelyan read and admired Akenfield, Ronald Blythe’s influential portrait of a village in rural Suffolk, which was also published in 1969. Like Akenfield, The Moon and the Sledgehammer does not simply offer a sentimental view of rural ways being crushed by industrial agriculture but reveals more troubling aspects of old country life, too. Mr Page is controlling and his daughters, Nancy and Kathy, appear trapped at home. There is also a suggestion of incest in one scene, beautifully shot from inside the house. Kathy is clipping roses and her brother, Jim, sings her a love song – “You are my garden of roses” – as Kathy giggles. “I felt that Jim and Kathy had a relationship of some sort which was secret, but I just don’t know,” says Trevelyan.

The Page family’s house in the Sussex woods

Trevelyan wishes he’d asked more questions – he was young, and young people don’t think to, he says – but he also fought his producer’s desire to return to the wood and probe the tensions within the family. “I didn’t enjoy asking them questions about themselves,” said Trevelyan. “That diverted me, and I wish it hadn’t.” He is consoled, however, by his ending: a shot of traffic being diverted as the Pages’ magnificent traction engine steams through Horsham. “The end is a triumph of family loyalty,” he says.

The family taking their steam tractor for a spin

Despite Trevelyan arguing fiercely with Vaughan over The Moon and the Sledgehammer – Trevelyan spent 18 months literally taping the film back together, frame-by-frame, after it was edited in a way that horrified him – the finished version only survived thanks to the efforts of Vaughan’s former wife, Katy MacMillan, who raised funds to buy the copyright and has reissued it on DVD. Trevelyan and MacMillan have worked together to digitally regrade the original and are now raising money so the 16mm film can be shown more widely.

The question every viewer asks is: what became of the family? Mr Page did not live long, and Peter, the eldest son, died in the 1980s. “They were all very much loved by local people. When Peter died, the whole village turned out, and a steam engine covered in flowers, and people followed it,” says Trevelyan. Nancy and Kathy moved into a council house together and did car boot sales; Jim lived on in the wood for a bit. Trevelyan visited 20 years or so ago but found it very run-down. He has lost touch with them now, and fears they may all be dead, but plans to call in on Kathy and Nancy’s old house when he travels to Brighton for the screening.

Trevelyan is “amazed” by the ongoing interest in his film, but believes that the defiant freedom of the Pages still resonates, nearly 50 years on. “Why the audience connect with it is a very interesting question,” he says. “They realise there is something free about the Pages that will never be in their lives, and perhaps should be.”

• The Moon and the Sledgehammer is showing at Brighton Festival, 4.30pm Sunday 29 May, complete with Q&A and traction engine.

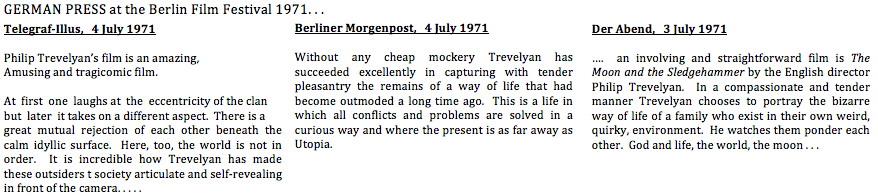

THE MOON AND THE SLEDGEHAMMER UK PRESS REVIEWS

__________________________________________________________________________________

“The film is quite unlike anything else I know, and should absolutely not be missed.”

-John Russell Taylor, The Times (London)

“Make a point of seeing Philip Trevelyan’s The Moon and the Sledgehammer. This hour-long encounter, hilarious but never patronising, with an eccentric family living in Sussex woodlands among traction-engines, harmoniums, tuneless pianos, roses and peacocks, gives a new brilliance to the word documentary. I have seen it twice but twice is not enough.”

-Dilys Powell, The Sunday Times

“I wrote a paean of praise for Philip Trevelyan’s The Moon and the Sledgehammer when it surfaced at the London Film Festival. Lack of space prohibits a repetition of that notice, but anyone who fails to see this extraordinary portrait of an extraordinary real-life family, the Pages, living in a ramshackle house in the woods near Horsham, is doing himself a notable disfavour.”

-John Coleman, New Statesman

“The Moon and the Sledgehammer is easily the best British movie I’ve seen for a long time. .It starts at the point where the best documentaries start – where it begins to tell us about ourselves and each other more than just the Pages – but for that you have to see the film”

-Verina Glassner, Time Out

“Trevelyan persuaded them (Pages) to let him film them – and I beg you to see the results. It’s a gloriously amusing sketch of how human nature left to itself, twists and turns in weird spirals of self-revelation like convolvulus round a bush. I repeat it’s a marvel of a film.

-Alexander Walker, Evening Standard

“. . . A documentary of enormous appeal, funny, compulsive to watch, and quite endearing. In a house without gas, electricity, or running water, Mr Page organizes a life that is as remote from suburban existence as that of a property millionaire or an Aztec king. . . The film is a wonderful piece of observation, neither sentimentalising or romanticising this off-beat way of life. It draws no conclusions, being content just to point a perceptive finger. I recommend it as a beautifully presented slice of reality.

– Ian Christie, Daily Express

|

|

|

Vertigo Autumn ’07 THE MOON AND THE SLEDGEHAMMER by Andrew Kotting

A CULTURE IS NO BETTER THAN ITS WOODS W.H. Auden

If you go down to the woods today you’re in for a big surprise…..

We’ve climbed a mountain and passed a valley of fear, there is thick woodland and in it a clearing. Butler’s Erewohn? Gun shots ring out. The camera explores the landscape, the fecund and verdant landscape. A closer inspection. Close-ups. Close. Smoke billows out of the cabin in the clearing. Skeletal car carcasses, buses, heavy metal inland flotsam and jetsam. A forlorn piano playing along to things pastoral. Probably discordant. Or is that the tinkersound of Tom Waits?

Who are these people?

More gun shots. Where are these people?

There he is.

Good evening Ladies and Gentlemen

Battered, beautiful and Beuysian besuited. Mr Page. No teeth, gnarled drift wood face, sump-oil soaked cigarette stuck to the corner of his mouth and welcoming. Stand back you boys as the elephant’s about to make water. Beuysian behatted. Of all the felt hats I felt, I never felt a felt hat like this felt hat felt.

We are in the world of Philip Trevelyan’s The Moon and The Sledgehammer. It is 1971 and the spell has been cast. It was maybe ten years later that I saw the film. Transfixed, it transformed the way in which I would make my own work. A template for the believable heaviness of making.

The Sussex landscape is the real place. But this is a thousand places, a thousand faces. I’ve stumbled across them in South America, The High Andes, Kenya, Madagascar and The French Pyrenees. All round England and back again. Wizened, weather-beaten, life-ridden oracles. And Richard Stanley (camera) has captured it in order that Trevelyan can make his magic. The father, the sisters and the holey sons beguile with Pagean banter (what happened to the mother?) Not cant but manna.

The world’s all to pieces, isn’t it? They’re like a lot of rats and mice in England. They don’t know what they are going to do. It’s a good job the moon’s well up there too, I’ve got room enough to swing a sledgehammer underneath him without hitting of him. He’s well out of my way. But if they had their way they’d get the moon down you know and they’d be trying to wheel him along the road on two wheels.

Man will invent thing to destroy himself. And it’s true.

But what I know other people will never know because I shan’t tell them.

Seminal aphorisms and insightful anecdotes, a glue for this their apparent nonsensical way of living. A portrait of a fantastical family at

odds with the world and then themselves. Scrap metal, steam-driven lumber-jacking self-sufficientists.

The film was my compass for Gallivant and my accomplice for This Filthy Earth. It has nurtured me and fed me. Jon Bang Carlsen must have drunk from the same trough, as his companion films It’s Now or Never (1966) and How to Invent Reality (1996) contain smidgeons of the same spellbinding. Ben Rivers’ This Is My Land (2006) is a magnificent pretender and then of course there’s Stalker…

If you go down to the woods today you’ll hardly believe your eyes…

The dvd is now available through www.themoonandthesledgehammer.com and Andrew Kotting’s In the Wake of a Deadad project can be seen at Dilston Grove, Southwark Park, London from October 4th – November 11th (visit

www.cafegalleryprojects.org; www.deadad.info).

OLD GLORY, July 2007 ‘Engine family’ film re-released One of the best-loved films to feature steam traction engines is now available for home viewing following the brand new release of the film The Moon and the Sledgehammer on DVD. Vaughan Films has released this much-loved 1972 film, which has been digitally re-mastered to the highest standard. A summer of the late 1960s found young film maker Philip Trevelyan in East Sussex. Philip, who had spent the last five years honing his craft making documentaries for the BBC and Granada Television since leaving the Royal College of Art’s Department of Film and Television, heard of the Page family through a mutual friend at an engineering works and decided to spent the summer with the family in their six-acre woodland home, cut off from society and progress, for the purpose of recording their outmoded self-sustaining lifestyle to film. The Page family consists of Mr Page, his two sons Peter and Jim and his two daughters Nancy and Kathy. Their seemingly eccentric lifestyle shows a family at one with nature, but at odds with society and each other. And for all their eccentricities they ably demonstrate that they are remarkably successful at looking after themselves in a way few of us are today. The Pages live in woodlands in East Sussex, in the heart of the commuter belt, about 20 miles from London. They have no gas, electricity or running water and manage to sustain a self-sufficient lifestyle; shooting game, keeping chickens and growing vegetables, and if cash is ever needed, undertaking mechanical work for local farms. One passion of the Pages is steam engines. Their land is littered with gigantic spanners, rusty iron carcasses, parts of old engines and disemboweled car bodies, but most spectacular of all are the traction engines (a Fowler and an Allchin, the latter of which is now in Ireland with Fred Jenkinson) that the men tinker with, discuss endlessly, compare merits of different engines and drive them thunderously around the woods to no apparent purpose, apart from the sheer enjoyment of it. The isolation of their location has allowed them to grow as individuals, where they can freely develop their own ideas about the world around them. Many of these ideas seemed somewhat eccentric when the film was originally released, but today seem like prophetic warnings from the past. Peter discusses the merits of steam power over oil, saying: ‘England ought to be run by steam. It’s all wrong to have motor power because the oil has got to come across the sea, and that’s too costly. Steam will beat the price of petrol. Steam will come back because it will get so that we shan’t be able to get no oil and petrol later on. That’s when steam will come in then.’ |

Mr Page talks of the dangers of television and radio, work and food, pros and cons of different pets, and tells us of the time he saw a sea scopium which he attempted to catchThe director skillfully allows the Pages to air their views on many issues, ranging from sledgehammers to the moon, so that a picture of their life and lifestyle slowly emerges, reminding us of a bygone time before we became part of today’s homogenized society. In fact, filming took place before the moon landing, which is quite an important point and makes sense of what Mr Page says about man getting to the moon.

The film showed at the London and Berlin Film Festivals to great critical acclaim. In film making terms it defied established boundaries – only natural lighting was used, there was no voice-over and the director allowed his subjects to tell their own story, having no previous agenda other than to bring this family’s lifestyle to film. In many ways it is counted among the first ‘reality’ documentaries. In an interview with The Sunday Times Trevelyan says: ‘As a film maker you are bound to honour your material. You must tell the true story that emerges – and that takes time. It’s the only way, though. If you go in with a cut and dried brief all you are doing is raping the subject.’ The Rank Organisation, at that time the UK’s largest cinema chain, wanted the new Warhol feature film Flesh in its cinemas. Through skilful negotiations Vaughan used this leverage and was able to secure a national release for The Moon and the Sledgehammer. It went out with Rentadick – Britain’s answer to the public’s growing demand for the removal of censorship. The coupling of these two films must surely have been one of the strangest in film history. However, as Rentadick was destined to be hugely popular, it meant that The Moon and the Sledgehammer was viewed by a large sector of the British public. If you weren’t around to see The Moon and the Sledgehammer first time round you can now purchase your own DVD. It’ a film that can be watched many times on many levels. There is always some new gem to be uncovered with each viewing. Running time 65 minutes, colour. Price £16.99 The DVD also comes with an eight-page booklet of filming notes and two postcards. Orders can be made via the film’s official website at www.themoonandthesledgehammer.com |

U.S REVIEWS Abridged

U.S REVIEWS Abridged

Read full reviews here

The Best Old Movies on a Big Screen This Week: NYC Repertory Cinema Picks, April 6-12

The Moon and the Sledgehammer (1971)

Directed by Philip Trevaylen

In the opening moments of The Moon and the Sledgehammer, the camera pushes aside branches and finds a clearing: the Page family residence, a few miles outside of London. Nobody’s home, so the camera has a look around, peering in for close-ups of the pianos, smithing tools and steam engine components scattered about the lawn, before the elderly Page patriarch emerges from the woods to deliver a ringmaster’s greeting. A tone of wonderment at a found object Trevelyan vérité-style but clearly pieced-together glimpses of Page—a circus clown turned self-sustaining woodsman, tinkerer and pipe organist—and his grown children, two feral gardener girls and two lost-boyish, passionately mumbling engineers, especially handy with old steam engines. Stray moments and pronouncements about sustainable lifestyles and overdependence on petroleum seem prescient—though the Page children are almost closer to the idiosyncratically socialized rural eccentrics in the phonetic dialogue scenes of a Victorian novel than today’s very in-the-know opt-outs. Ultimately this is family portrait, too specific and singular to be anything but a curio first and foremost. As a curio, though, it offers up gorgeously strange images, moments that take no set social rule, technological advance or natural relationship as a given.Mark Asch (April 9, 6:15pm at the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s “Art of the Real,” introduced by filmmaker Ben Rivers)

Film review Critic’s Rating 4/5 STARS

Film review Critic’s Rating 4/5 STARS

The Moon and the Sledgehammer

Dir. Philip Trevelyan. 1971. N/R. 65mins. Documentary.

They seem at first naive about the ways of the world, but Trevelyan captures something poignant in their uncluttered harmony with the land. Mr. Page scoffs at these imaginative ramblings, less because he’s uninterested in the heavens than because he sees more that’s worth cherishing in his wooded oasis. He may be right—and that’s what makes this bizarre biography so unforgettable.—S. James Snyder Read full review here

| The Moon and the Sledgehammer by Andrew Schenker |

![]() ***BEST NEW OLD RELEASE OF THE WEEK***

***BEST NEW OLD RELEASE OF THE WEEK***

The Moon and the Sledgehammer (Anthology Film Archives) — This lost gem from the early 1970s casts quite a hypnotizing spell as it profiles a truly eccentric English family living on an estate in the country. The Moon and the Sledgehammer is a lovely lesson in how to turn a potentially exploitative subject into something much more tender and poetic

Movies

True Escapism in The Moon and the Sledgehammer

True escapism this summer is to be found with the Page family in Philip Trevelyan‘s 1970 steam-engine idyll-doc. The seclusion is just as much an effect as a reality, and the resulting world and its garden of metaphors for the artistic pursuit have influenced outsider admirers and experimental filmmakers..