The Films: Philip Trevelyan in his own words.

Philip Trevelyan talks about his films: a rare opportunity to know better what the film maker had in mind when preparing, filming and editing his work. Learn about the background to his films and the historical social setting that dictate the present and why the subject matter is so important to him.

The Moon and the Sledgehammer

Directed by Philip Trevelyan

UK 1971, DCP, color, 65 min

This film is a brief encounter with an unusual, complex family who retreated to the woods, working primarily as agricultural contractors and engineers. In the summer months they also provided steam and electrical power for the circus; the family’s father, Mr. Page—affectionately known as “Oily Page”—even became a stand-in performer in the ring. Influenced by the book of Revelations, the family was suspicious of society and progress. The development of modern agriculture in Britain’s postwar drive for cheaper food removed people from the land. For Mr. Page, this social tragedy and waste was exemplified by the idea of sending people to the moon, which was about to happen when the film was recorded. However, alongside the suspicion and unhappiness that grew out of the family’s retreat from society, they never let go of a simple, infectious enjoyment of life. This is captured by the grown-up children’s re-enactments of happy times or by the youngest son when he describes the sound of steam engines, climbs trees, or tells us that he has observed the moon through a homemade telescope.

Lambing

Directed by Philip Trevelyan

UK 1964, 16mm, b/w, 26 min

This is a film about a traditional Sussex shepherd whom we follow from morning to night, through snow and wind, as he works alone with his flock. This was my first proper journey into filmmaking, and my subject was a person I had worked for and admired as a boy. We used an Arriflex camera with fixed lenses and occasionally resorted to a simple wind-up camera. No electricity was used for any lighting and all sound was “wild.”

The film is constructed from carefully edited moments in the shepherd’s routine work. His passing comments about how to deliver or feed lambs are our only guide. He sometimes reflects on the difficulties he encounters, such as the deaths of lambs or the bitterly cold snowfall. On the whole, we learn that he loves his work and that he is happy when resting in his chair by the fire, making a cup of tea or warming milk for the orphan lambs. If the film has a climax, it is captured in the struggle of a ewe giving birth to its lamb. The film ends as the evening turns to night and the shepherd returns to his chair by a warm fire: he pulls a blanket over himself and quietly sings himself to sleep. Print courtesy the filmmaker.

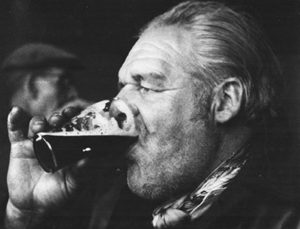

The Ship Hotel – Tyne Main

Directed by Philip Trevelyan

UK 1967, 16mm, b/w, 35 min

Initially, I took still photographs and wrote notes on my visits to a special and intimate riverside pub, used by engineers, ex-coal miners, factory workers and their families. The beer was cheap and well kept, singing was always encouraged and the people were close friends. There were several tales about the pub being a meeting place for lovers; I decided to add it to the purely documentary material, so the film includes three local friends who re-enact this element.

The film takes place on a Sunday, and the landlord and his wife rise early to prepare themselves and the pub for the day ahead. We see their regular customers arriving, people at the darts board, the pub gradually filling. Suddenly we meet two retired coal miners competing at dominoes. Old Tina watches the fire and enjoys a dance. Her presence provides a vehicle for reflection in several scenes. The film reaches a climax when the pub is full, the mouth organ is playing, and the singing and dancing reaches its height. It calms down when the landlord and his wife sing their love song. Before this, we have observed “Dicky,” the tattooed “rag and bone” collector, who lives alone and uses a horse and cart for his work: he is a legendary figure, partly because he once swam the river Tyne in winter, for a bet. At the end of the film, he walks out of the pub towards his home and stops for a moment, to silence a small example of the technology that interferes with the world that he knows. Well warmed by the drink, he wanders into the uncertainty of a foggy night….

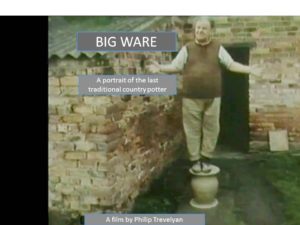

Big Ware

Directed by Philip Trevelyan

UK 1975, 16mm, color, 40 min

This is a record of the last pottery in England that made the everyday pots that households and businesses have used for centuries. The potter, Mr. George Curtis, remembers that, in his youth, he helped fill whole railway-goods carriages with earthenware pottery. Even as the film was being made, his orders included huge numbers of nesting bowls, made especially for the racing pigeons kept in lofts by the working people of Northern England. The last man to be continuing the tradition, Mr. Curtis digs his own clay, prepares it, throws it, fettles it and fires it in his kiln. His performances at the pottery wheel demonstrate powerful and extraordinary skills; George’s modest claim to fame is his throwing speed, which kept him in work throughout his life. His enthusiasm and knowledge are infectious, while the craft itself is fascinating. The film follows him while he talks us through the various tasks. Toward the end of the film, he taps the fired pots as they come out of the kiln: “You can always tell a good pot by the sound of it.” All that he shows us rings true.

K. 491 in Preparation

Directed by Philip Trevelyan

UK 1983, 16mm, color, 55 min

The treatment for this experimental production was based on the idea that before a musical performance, principal players work on their parts and that their private practice allows them a deep exploration of the music. As an amateur bassoon player, my own practice suggested that this was often true. Could this interior feeling be conveyed on film? There were three conditions imposed on the production: every note of the musical score was to be played, there were to be no words, and the programme (which was commissioned by television) had to be an hour long.

Everything takes place in and around the venue for the concert, which is an imposing 18th century house. I knew that the pianist would be practising on the piano in the house and that, because the orchestral members were staying in the same house, it seemed likely that they might also practice, albeit in separate rooms. My idea was to join together the pianist’s solo work with the string and wind players’ practice in a sequence of continuous musical coincidence. Meanwhile, I noticed that farmers and shepherds were also busy with their work outside. It felt to me that these two worlds could be shown to coexist, and that collisions between the inside and outside activity might add an extra dimension to the production.

Basil Bunting

Directed by Philip Trevelyan

UK 1982, 16mm, color, 60 min

A lot of this production had been beautifully shot by members of the Amber film co-op, when I was asked to shape and edit the material. The film is based on Basil Bunting’s magnificent recording of his autobiographical poem “Briggflats.” Bunting believed strongly that the sound of poetry being read aloud was far more informative than extracting meaning from the page. The poem refers to the rhythm and sound of Scarlatti’s music: it takes us on journeys through aspects of Bunting’s extraordinary life: his life as a Quaker and as a conscientious objector (1918), as a sailor or in Italy with Ezra Pound, and in Persia where he was an Intelligence officer, Timescorrespondent and assistant to the consul. But above all, the poem constantly returns to his adolescent love for a young girl in the North of England, where the heart of the poem resides.

While editing, I separated Bunting’s reflections on poetry or quiet thoughts on life from the progression of the poem; sometimes the gentleness of his voice turns these words into a form of poetry. At one point, we accompany him on his journey to “Briggflats” where much of his adolescence was spent. As his little car speeds through a big landscape of northern hills, Bunting’s wonderful rendering of the poem recalls ancient kings, their legendry battles for land… and his own relentless search for the truth.